When I started this newsletter, one of my goals was “publishing demystification.” Publishing itself is often needlessly opaque, and even seasoned authors often repeat wildly inaccurate myths about sales, genre, and other aspects of the book world. So I’ve been reading with interest the series of arts data articles produced between the Post45 Data Collective and Public Books called “Hacking the Culture Industries.” They’ve produced several interesting book-related articles on the New York Times’s coverage of black authors, the diversity of New Yorker fiction, how bestseller lists are calculated, and the obscurity of book data.

That last article, by Melanie Walsh, was especially interesting to me. The article looks at how hard it is to find accurate book sales data—I went into depth on why book sales can be so confusing here—and makes good points about the ways more access to book sales could be of help, especially to academics.

But, since I believe the goal of this series is to spark conversation, I hope the authors of this series won’t mind my posting a few disagreements. Because two comments made my eyes bulge a bit too far out of my head.

The first is the stated general mission to “to make book data (and other kinds of cultural data) free and open to the public” and in particular calls to make BookScan data public. As an academic, I get the impulse. I’m sure there are many interesting topics academics could explore with better book data.

But as an author, dear god, please do not make BookScan data public!

Absolutely the first thing that would happen if sales data were public would be people mocking authors on social media with screengrabs of their poorly selling books! A site like Twitter would be absolutely filled with sales dunks and comments like “Why I should I listen to some blue check loser about [any topic] who only sold 600 copies of their book!” This would be especially true for marginalized authors, who could easily be hounded by bad faith right-wing trolls.

Let’s be honest: most books don’t sell many copies. At least not compared to video games, movies, music, or most other cultural products. Even award winning books sometimes only sell a few thousand copies. Some of that is because not many people read and some of it is because so MANY more books are published in a year than movies or video games are produced. Either way, I guarantee most people not exclusively reading Colleen Hoover books would be shocked by the sales of their favorite authors. And then, as the article explores, BookScan itself is extremely partial making already small sales numbers even smaller. This isn’t BookScan’s fault per se, it’s because getting accurate book sales data is hard and complicated.

Still, I do worry people weaponizing sales data against authors they dislike would dwarf any other use the public has in getting open access to admittedly partial data. And frankly I’d bet more than a few readers would simply write off books they might have loved just because they didn’t sell well. Why read a novel only 1,000 people have read when you can read one 1,000,000 people have and, even if you hate it, at least you can join in the conversation and be rewarded by social media algorithms?

But there was a more interesting set of questions that have stuck in my mind:

To what extent might BookScan data—with all of these holes and inaccuracies—be shutting out imaginative and experimental literature? To what extent might BookScan data be shutting out writers of color—or anyone, for that matter, who doesn’t resemble the financially successful authors who came before them?

To be clear, the article doesn’t make the claim that accurate data would produce more imaginative or diverse literature. But I’ve seen this sentiment many times before and since the questions were posed I’ll give my answer:

Nope.

First, I’d suggest the article seems to make a logical leap from saying BookScan gives an imperfect sales portrait (true) to assuming publishers don’t have a more accurate one. While book sales data aren’t public, the big publishing houses do keep their own sales records in addition to using Bookscan, as well as expending additional resources trying to understand what books sold what, market trend analyses, and so forth. Penguin Random House is not groping in the dark.

Moreover, I agree with John Warner at Biblioracle who said “focusing on the number of books sold is more likely to narrow, rather than expand the range of what gets published.”

Sales data won’t save art. Not in a capitalist world. Nor in a racist, sexist, classist, and (etc.)ist country. The inequalities of America are of course reflected in book sales like everything else. That’s not to say that publishing couldn’t do a lot better with, say, marketing novels to non-white readers—something BIPOC authors talk about frequently—it is only to say that even more focus on existing sales is likely to increase inequalities.

As for the hope that more experimental work and more imaginative work would be encouraged by more focus on sales data, well, that seems like a fantasy. Experimental novels—and vital if poorly selling categories like translated literature and poetry—are not under-published because of inaccurate BookScan data. They’re under-published because a relatively small number of people read them. According to one stat, a mere 1% of fiction and poetry sales are of translated literature. The numbers for poetry are similar. And the translated literature and poetry that does sell is normally not the most experimental, innovative, or challenging. There’s no way to measure “experimental” sales, but, well, hell, take a look. Does this week’s bestseller list look diverse or experimental to anyone?

This is why experimental story collections, translated novels, poetry, and so on, are easier to find on non-profit presses than corporate publishers.

The artistic work that is published by the Big 5 corporate publishers can also be a labor of love rather than one of sales data. For all of publishing’s problems, and it has plenty, it’s still an industry with lots of people who love literature. Many imprints will acquire books they think are important that they know are unlikely to sell well. Indeed, getting to publish something you care about can be a reward for publishing the blah books that keep the company afloat. And if that sounds too idealistic for you to believe, then assume these publishers acquire these books with an eye to awards season, just as Hollywood studios put out a (decreasing number of) awards-hopeful films between non-stop corporate franchise IP sequels and reboots.

Everything in our culture—every social media algorithm, every corporate ad buy, every “poptimist” influencer—wants us to narrow the possibilities of art. To make our culture smaller and smaller, and thus easier to control and profit from. Art with any value, that pushes us toward new experiences and new ways of seeing the world, is always a struggle against the odds.

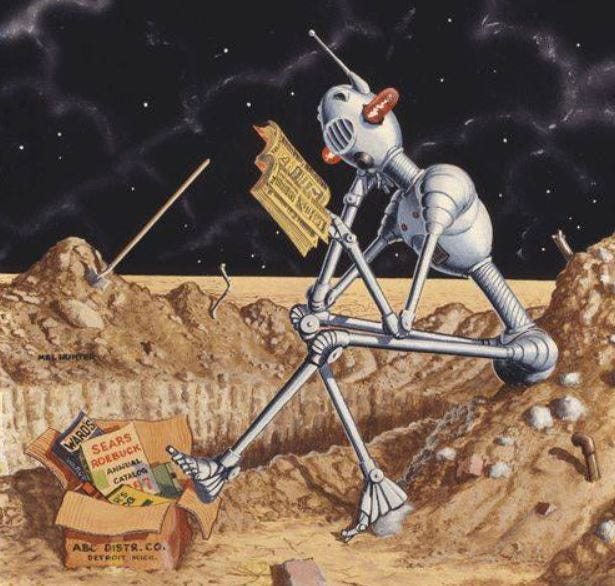

Hell, these days even the idea of art is mocked. The perfect example floated through my Twitter feed as I was drafting this post. Here’s a popular Twitter account furious that—for once—a corporate superhero film got some negative reviews and angrily mocking critics “who sit around…saying movies are art.” (The horror!)

Instead of spending more time focusing on sales, the best thing we could do as authors is write what feels vital to us; as editors, champion what we believe deserves to be championed; and as readers, seek out what no one else is reading and—if you love it—tell your friends.

As always, if you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”

All I can say is ughhhhhhhh to all this. I'm finding the academic series of articles you mention fascinating but absolutely agree that sales data being public to all would be...well. Yeah. Everything you said. It's so frustrating to see the way we've moved from the term artists to the term creators with the implication being that creators create *content* and *entertainment* but NOT art because art is for snobs. Or something.

great commentary and thanks for the links to those articles up top. I agree making Book Scan data public is dangerous, BUT, why couldn't a registered author at least understand sales statistics in their subcategory?