Art Should Be a Doorway, Not a Mirror

Some thoughts on Isabel Fall, social media criticism, and the puritan art police

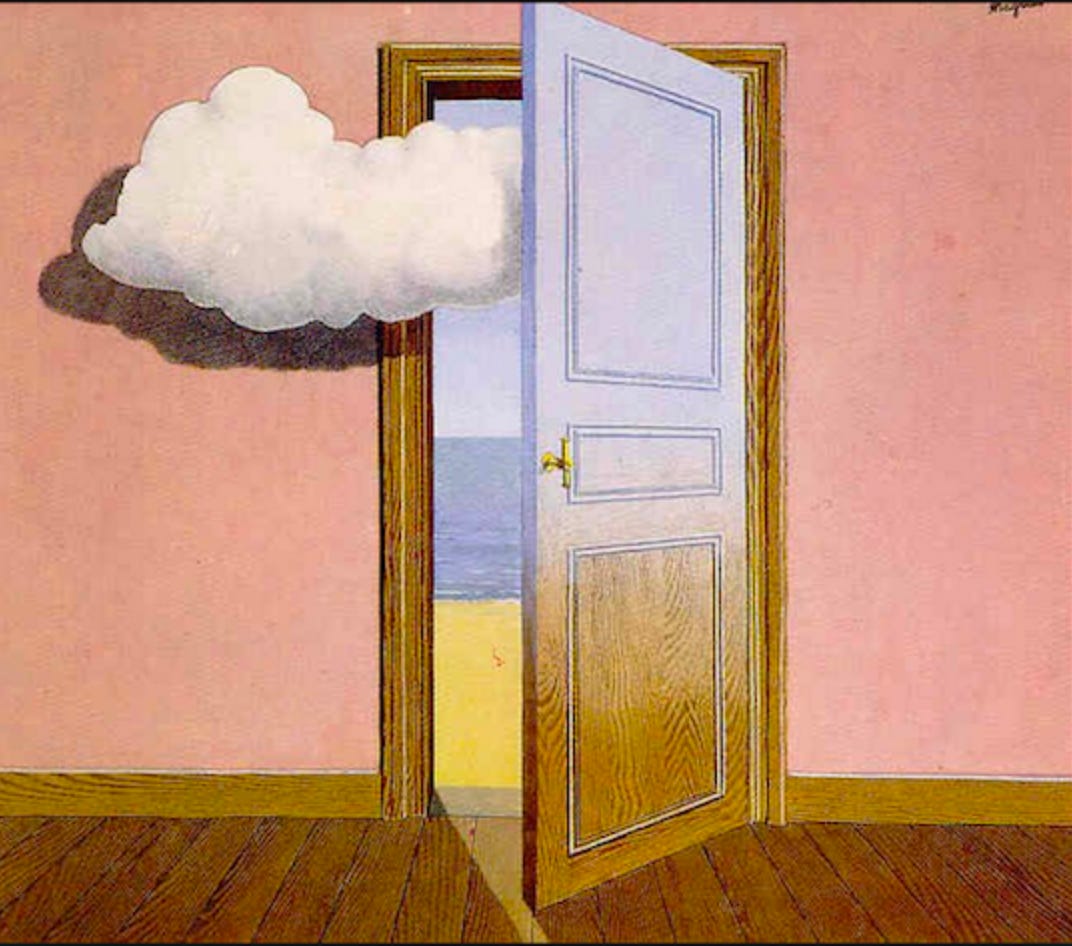

Like many writers, I grew up feeling alienated. I was, as the kids now say, neuroatypical (ADHD), bullied, and more generally living in the ruralish South surrounded by jocks, cops, Confederate flags, and self-righteous Christians who told me I was going to burn in hell on the bus ride to school. What saved me, if you will, what made me feel I had a place in the world wasn’t school or churches or sports. It was art. Specifically messy, dark, angry, transgressive, ambiguous, and strange art. It was punk rock and hip-hop and horror and SF and Surrealism and Franz Kafka. This was the art that let me be seen, but it was also the art that let me see. The art that gave me new ideas. That showed me new possibilities. That opened doorways to new spaces.

This isn’t a sob story. I didn’t have a notably hard childhood. I was still white and male in a world that privileges those things. I had friends. There was ice cream and balloons. Etc. Nothing about this is even unusual. Every artist I know, at least the ones worth a damn, have some version of this story. We were outcasts and we found our art. The artists I know who had it much harder than me—whose families or sexuality or backgrounds or bodies were marginalized and mocked by the dominant culture—were the most in need of messy and complicated art. They needed it to experience, and they needed to create it themselves.

So what I’m saying is that I believe deeply in the power of art. How it gives people access to spaces where they can explore, think, and exist.

And I’m still angry about what happened to Isabel Fall.

If you don’t know the story, last week Emily VanDerWerff at Vox’s wrote an excellent and detailed article. Here’s the short version of the story, as I understand it: An unknown writer named Isabel Fall published a short story in Clarkesworld repurposing a right-wing meme about people identifying their gender as helicopters into a dystopian SF story that explores gender, violence, and militarism. Critiques of the story started to build online, perhaps initially from trans readers but quickly being taken up by cis writers—many of whom would later admit they never even read the story—and snowballed into a social media mob who declared the writer an anti-trans, anti-woman, right-wing bigot.

Fall was in fact a closeted trans woman. The dogpiling of strangers, including some well-known SFF authors and industry gatekeepers, ended with her “check[ing] into a psychiatric ward for thoughts of self-harm and suicide.” Now, apparently, she has decided to stay in the closet. It’s all incredibly sad and infuriating. You should read the Vox article if you haven’t already to get the full picture and hear Fall in her own words.

Not that this is the most salient point in the whole horrible mess, but it should be noted that Fall’s story is quite good. It is vibrating with energy. The prose cackles and crackles. It’s messy and ambiguous and trying to grapple with complex things. It is exactly the kind of art that many people need to read to exist.

The Isabel Fall fiasco is hardly an isolated incident, even if its outcome was worse than most. There’s a rising wave of attacks on art and authors often involve not just misreadings or bad faith readings, but no readings. Actually reading the work in question—beyond perhaps one out-of-context screenshot—is no requirement, apparently, for attacking the author, demanding work get pulled, and requesting public flagellation. (There are countless examples, but I wrote about some recent ones here.)

Much of the issue is, as VanDerWerff says, with social media. Algorithms reward outrage and promote out-of-context readings. Social media dogpiles are a mixed bag of course. There are certainly some earnest critics who want an honest respectful dialogue but also plenty of bad faith bullies riding a thrill of borrowed self-righteousness. My sense, too, is that many simply feel pressure to weigh in. They don’t have time to fully understand the issue, but they want to lend support (or else are afraid of being targeted next).

Still, at the core of these mobs is a belief that art needs to be policed in order to protect consumers from being “harmed.” Every art policer from Plato to the PMRC has attacked artists in the name of protecting innocents. Yet who the innocents are is vague. Few ever claim to be themselves harmed by reading, say, a short story in an online magazine. I’ve never seen anyone say that reading a “bad line” in a novel changed their own political stance or warped their own moral center. Indeed, many of Fall’s critics made pains to say they liked the story even while calling for its removal. The concern is for some hypothetical gullible and sensitive reader who will be damaged by reading wrong lines, bad representation, or ambiguous plots.

The ostensible ideologies of these art police run the gamut from conservatives like Jerry Falwell to centrists like Tipper Gore to self-professed progressives and leftists. But what unites these people is aesthetic puritanism. They view art as a series of moral lessons that must be entirely unambiguous. Reading the tweets during these scandals, you see the same claims over and over again. Stories must be uplifting, characters “likable,” messages clear, and all bad or messy or immoral lines/characters/events must be explicitly rebutted in the text. (At times you sense they want the author to write “this is bad!” and “this is good!” in the margins of every page.)

This positions art not as a space of exploration, challenge, and mystery—not a doorway to new spaces where we can grow and change—but instead as a mirror to perfectly reflect one’s values back to oneself.

Historically, puritans start with claims of protecting children. From video games, from rap music, from heavy metal, from queer sex, from dark fiction, from etc. In books, of course, this means children’s literature and YA. There was recently an article from YA insider Nicole Brinkley on the toxicity of the genre called “Did Twitter break YA?” that’s worth reading:

But digital purity culture combined with the ideologies around YA books leave no room for nuance. Teenagers, after all, must be taught. Any action that is less than perfect must be labeled as a bad idea, or else you’re encouraging teens to mimic that behavior. It’s so prevalent an idea that tweets in which someone, for example, advocates that Brett Easton Ellis’ American Psycho should have included chapter-by-chapter disclaimers of its protagonist’s behavior can be interpreted both satirically and in earnest.

But what started in children’s literature is spreading to all corners, even those very spaces—such as SFF—that used to be where the outcasts and misfits called home. The very places they went to explore their complex and messy feelings.

I’m not sure I can phrase it better than Chuck Tingle did on twitter: “DO NOT GATEKEEP THOSE IN NEED OF A HOME […] the harm of a possible scoundrel slipping through the gate does not even come close to the harm you will cause by denying them entry and when you do that YOU have become the villain of your own story.”

Although this particular flavor of art puritanism claims to be progressive, their insistence on purity tends to harm exactly the people they claim to be protecting. It is queer authors like Isabel Fall who must out themselves, or victims of sexual assault like Kate Elizabeth Russell who are pressured to publicly state their trauma in order for their fiction—remember what that word means?—to be permitted.

Of course, I’m not saying anything here that a million marginalized authors haven’t written about before. Here’s Princess Weekes, writing about what happened to Isabel Fall in The Mary Sue:

As a Black queer woman, I’m frequently almost paralyzed with fear about the question “Am I doing justice to Black folks like me?” I know that I cannot write for every Black person; I know Black people are not a monolith, but I also fear making Black people look bad. Or simply just not doing enough. Those things don’t make me more creative. They just make me drink.

All of this is of course a result of a racist, ableist, sexist society. That’s the root cause. But that doesn’t mean the art police aren’t making it worse.

Does art itself cause harm? Perhaps. But one thing that’s hard to ignore in these episodes is the wide gulf between the righteous outrage and the actual stakes. Although as a fiction writer it pains me to say this, very few people read fiction. Even fewer read short fiction. Only a tiny number read weird SFF fiction published online. A science fiction short story is not a billion-dollar Disney movie. It is not a hit TV show with millions of viewers. It’s certainly not Republican legislatures or Supreme Court rulings or military campaigns. What does it really mean to claim a short story read by a few hundred people (if that) is “normalizing” anything?

As Ottessa Moshfegh said recently: “Novels like American Psycho and Lolita did not poison culture. Murderous corporations and exploitive industries did. We need characters in novels to be free to range into the dark and wrong. How else will we understand ourselves?”

Art is an opt-in feature of life. This is especially true of experimental fiction. Outside of school, no one is forcing you to read a short story. No one is holding a gun to your head demanding you recite a poem. Art can open up vital spaces for those who need it and seek it out, but what effect can it have on those who don’t?

Here’s a quote from Fall herself that I can’t stop thinking about:

“I don’t know what I meant to do as Isabel,” she says. “I know [that publishing “Attack Helicopter”] was an important test for myself, sort of a peer review of my own womannness. I think I tried to open a door and it was closed from the other side because I did not look the right shape to pass through it.”

I don’t know what counts as harm to a reader, how that can be measured or quantified. Here’s something I do know though. It’s unlikely that the critics of Isabel Fall’s story thought much about the story in the weeks or months after their attacks. It’s equally unlikely Fall will ever get to forget their attacks.

Does this mean art can’t be criticized? Of course not. Art needs criticism to thrive, and there is certainly plenty of hateful, racist, sexist, and otherwise bigoted (or just badly made) art out there quite deserving of our scorn. But there is a difference between criticism and harassment. There is a difference between attacking bigotry and in demanding that art be unambiguous is its moral messaging. There is a difference between art—beautiful, strange, complex, and messy art—and Goofus and Gallant comic strips.

Even now, Isabel Fall’s harassers admit that what happened to her was awful but, fundamentally, many still say it was her fault. She should have provided more context. She should have provided proof of her identity. She should have chosen a different title. She should have scrubbed away all ambiguity and messiness so no one could possibly misinterpret her work.

This is an absurd, anti-art position for several reasons, not least of which it is impossible to police every reader’s response. People will always take what they want from art, even the opposite message of what was intended. Capitalists and fascists favorably cite socialist (and literal anti-fascist solider) George Orwell’s allegories. Few bands had more overt leftist messages than Rage Against the Machine, but that hasn’t stopped Paul Ryan from loving them. And there are plenty of reverse examples too. J.K. Rowling is in real life transphobic, but many trans readers still took meaning and solace in Harry Potter as children.

There is simply no way to control everyone’s response to art.

The part of Emily VanDerWerff’s article that I’ve seen screencapped the most is this passage:

The delineation between paranoid and reparative readings originated in 1995, with influential critic Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. A paranoid reading focuses on what’s wrong or problematic about a work of art. A reparative reading seeks out what might be nourishing or healing in a work of art, even if the work is flawed. Importantly, a reparative reading also tends to consider what might be nourishing or healing in a work of art for someone who isn’t the reader.

This is a useful concept that gets at one of the most infuriating things about the puritan art police: they insist that their preferred art is the only type that helps people. They can’t conceive of any other way to experience art. Any other spaces that art can create. Any other ways it can heal.

They only know art as a mirror, never as a doorway.

The kind of sterilized, cellophane-wrapped fiction they seem to want—scrubbed free of all nuance, complexity, darkness, and grit—has always been, for me, the most alienating work at all. When I was bullied or mocked or depressed, the absolute last thing I wanted was Chicken Soup for the Soul. I didn’t want “uplifting” stories where the good always win, characters are always likable and unproblematic, thoughts are never dark, humans never messy, and no one is ever hurt. There was no room for me or my feelings in such work.

Maybe that is the art that some people need. Maybe that does heal some people. At the very least, it sells well. That’s all good! As I said, art is opt-in. It’s very easy for me not to read such work. Unlike the art police, I’d never demand that it be censored and those artists beg public forgiveness. But the idea that their view of art is the only one that heals people is what I take issue with. The idea is, yes, harmful. It, yes, normalizes the feeling that anyone different is bad, wrong, shameful.

And perhaps above all it makes artists afraid to make art. So many artists I know—especially less privileged ones—experience what should be their happiest artistic moments, such as a publication in a great science fiction magazine, with dread. They worry about Twitter pile-ons and Goodreads one-star review bombs. And, sadly, many do scrub their work of its complexity and messiness. The upsides of a few Twitter likes and a small honorarium that won’t cover rent are hard to weigh against the risk of harassment that can destroy your mental health, career, or even life.

So less art gets made, and what is made is less vital. And consequently, there is less space out there for the weirdos and outcasts to exist in. The kind of art that Isabel Fall made, the kind of art that has always spoken to me, is a doorway to new spaces. It makes the world a larger place. Those who want to fence in art and patrol it and limit access to it are making it a smaller and smaller one.

Thanks for sharing this thoughtful piece, Lincoln. I’m wary of an increased focus on the author (akin to a brand or commodity), and how “who” the author is relates to the author’s work. If this focus obstructs or stifles creativity, then it makes sense that some authors (who have steady offline followings) stay away from social media. Going forward, I wonder if writers will be able to succeed as authors and maintain privacy, or if one comes at the expense of the other.

Thank you. So much. There are so many talented writers these days who are straight-up scared to write anything because they fear the angry mobs.