I’ve had a short break from updating this newsletter, in part because, well, the state of the world. But mostly because I’ve been in the revision mines—more specifically the “first pass” mines—on my forthcoming novel, Metallic Realms. I will not ramble about that book here, but it got me thinking about the fun yet fraught process of revision.

Revision is both the most exciting and somehow the most depressing part of writing, at least for me. Revision is where everything comes together—where the seeds you’ve planted in the rough draft soil sprout into an actual garden, or where the blueprint design is turned into an actual building, or where [insert your own metaphor]—it is where a draft becomes a book. But this also means it’s where all the open possibilities and exciting permutations of the book are shut down, one by one. Where the infinite multiverse potentialities are sealed off until only a single timestream remains.

(Excuse my science fiction metaphors. I’m still in the headspace of Metallic Realms, which revolves around a group of wannabe science fiction writers.)

George Saunders talks smartly and honestly about how revision is “much more mysterious and more of a pain in the ass to discuss truthfully” than writers admit. It’s easier to talk in vague metaphors, as I’ve done and Saunders does too—although I quite like his comparison to a man building “a model railroad town in his basement.” He makes many small adjustments to the figurines and buildings based on what he simply thinks feels right. It is a largely intuitive process. Tons of adjustments made until it seems done.

How does one actually revise a novel? Each writer must find their own process, and perhaps even a different method for each project. Still, let me move away from metaphors and also abstract talk of “finding your voice,” “implementing a vision,” or “expressing yourself” to talk about practical revision tips.

We might say most writers tend to either be cutters or expanders. If you are a “loose” writer who pumps out messy drafts, your revision process might be primarily sculpting by deleting. Stephen King in On Writing said his life was changed when a teacher gave him this very prescriptive feedback: “Not bad, but PUFFY. You need to revise for length. Formula: 2nd Draft = 1st Draft – 10%. Good luck.” I know more than a few writers who follow this advice. They set a goal of cutting roughly 10% for each new draft.

Other writers will draft more skeletally, and the work of revision will be expansion. This was the case for me when I wrote The Body Scout, which was in part a book I wrote to teach myself how to write an actual plot. (Not something I learned in my creative writing courses, I’m afraid.) Because of that, my first draft was focused on getting down the essential character beats and plot points for each chapter. Revision was fleshing out the scenes with description, interiority, and the rest.

But whether you write skeletally or loosely in your draft, one method that I personally find useful in revision—and this will involve another metaphor I fear—is adjusting your narrative levels.

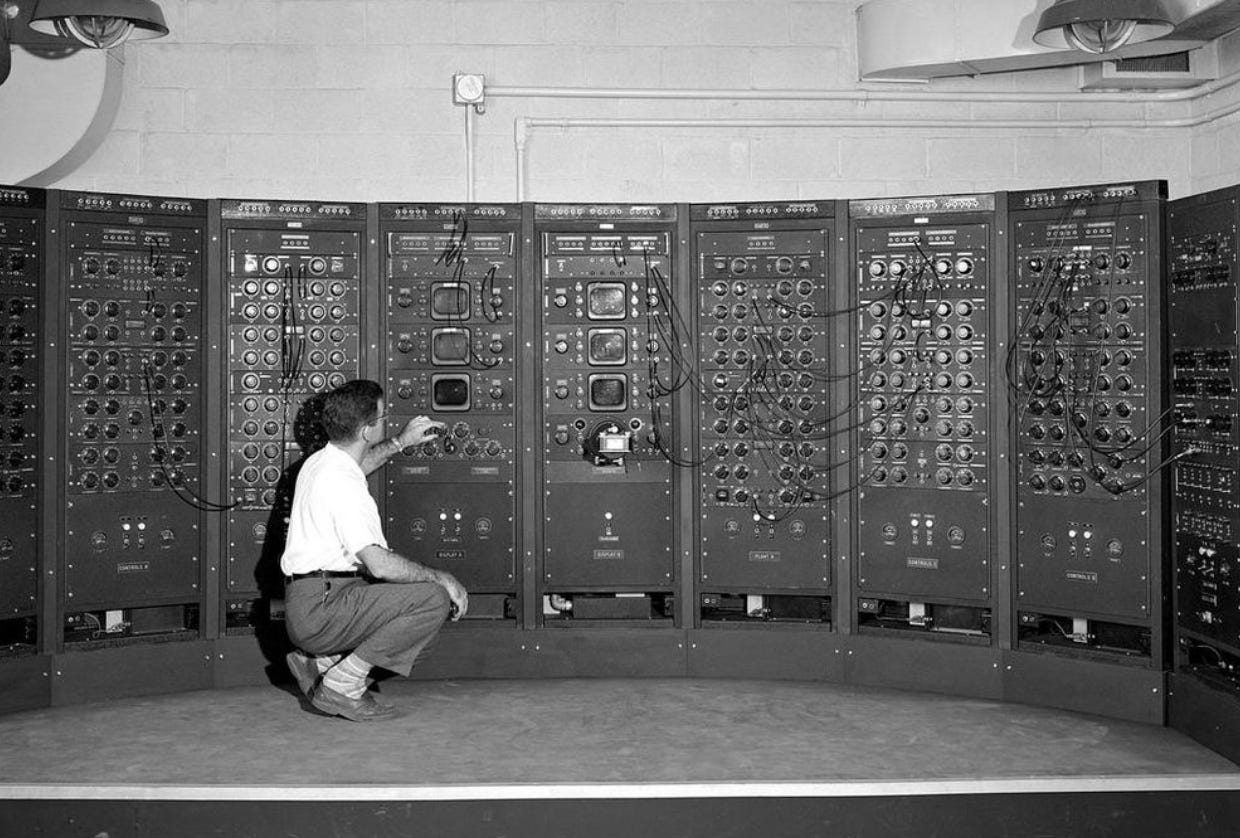

Imagine a gigantic science fiction machine with a bunch of dials. One dial says DESCRIPTION, another INTERIORITY, and others DIALOGUE or ACTION and so on. The basic narrative elements, however you might define them. In revision, it can be useful to look at each chapter or scene and see how your levels are doing. Does this scene need more setting? That one less action? Is dialogue cranked up too much in chapter 2 compared to chapters 1 and 3? Crank your dials accordingly.

This “adjustment” process should be done at both the level of scene and overall novel. One should look at the balance of each given section, and also the overall shape of the story. Do your levels suddenly switch midway through the novel, and a book that was heavy on physical action suddenly become entirely interior? Does your snappy dialogue disappear after the first third? Is your evocative setting details all stuffed in the second half? Time to tweak and turn.

Obviously there is no “correct” way to write a scene or a chapter, much less a novel. The beauty of fiction is it can take an infinite number of shapes. Your levels will depend on your personal aesthetics, your goals in a given work, and perhaps also the genre you are writing in. Some excellent novels are entirely dialogue, for example, while others have little or none. A noir novel may have the VOICE dial at max while a Gothic novel perhaps puts ATMOSPHERE up to eleven.

But for most novels, consistency is desirable. That might mean an even mix in every chapter or it might mean making sure your book is consistent in its uneven levels. You may look at your chapters and think, “Oh, the creepy atmosphere in this horror novel really falls off in chapters 4 and 5. I need to add in more eerie description.” Or you may say, “Crap, chapter 2 is all interiority while chapters 3-6 have almost none.”

Obviously, there can be good reasons to have a chapter 2 that’s all interiority while surrounding chapters have none. But there probably does need to be a reason. It shouldn’t be because you merely wrote a lot of dialogue on one day and a lot of interiority on another day without ever thinking about the balance of your piece.

I like this “mixing board”—to tweak the metaphor slightly—thought process because I think many emerging writers don’t necessarily think about narrative balance. If they are a “literary” writer, they tend to look at a story line-by-line in revision. Is this sentence beautiful? Is that observation as witty as I initially thought? Does this simile sing? If they are a more commercial-minded writer, they may focus on well-constructed plot beats and character notes. All of that is good and important. Who doesn’t want well-plotted and lyrically written novels? But it is also important to step back. To look at the shape of each scene and the overall structure they make when stuck together. Are the parts balanced in the way you want them to be to achieve the effects you want? Does the novel feel carefully and consciously constructed from start to finish? Narrative balance isn’t a big focus of creative writing classes or how-to-write-a-novel guides. Yet the reader notices, consciously or unconsciously, when a story feels sloppy and unbalanced.

If you like this level-adjusting revision method, there are two broad ways to implement it. One is what I’ve described. Look at the narrative mix of each scene, each chapter, and then the whole book. Adjust as needed. Another method is to go through dial-by-dial so to speak. That is, do a pass through the novel looking only at dialogue. Then a revision focused only on setting description. Then a revision only looking at interiority. So on and so forth until it is done.

This level-adjusting method can be useful in revision, but as supplement and not replacement to other revision techniques. You still need to carefully plot your story and polish your prose. You still want a sound structure, memorable characters, lovely sentences, and so on and so forth. Hey, no one said writing was easy. And once you are done? Well, you start all over again.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout—which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent”—or preorder my forthcoming weird-satirical-science-autofiction novel Metallic Realms.

Great post, I'm wondering how the mixing board metaphor applies to revising short stories. Perhaps the soundboard has fewer dials when it comes to a short story?

Useful metaphor I just stole from you. 😇 Thanks!