Writing Terror into Your Horror

Some October horror writing advice to curdle blood and tingle spines

It is that time of year again. The leaves wither and die, a cold chill runs down your spine, and at all hours the horrible repetitious howls of gibbering monstrosities drive mortal men to madness! Yes, I speak of political pundits during an election season. But enough of horrors. Let’s talk about horror fiction.

I’ve written before about “the spooky spectrum” of horror fiction effects, such as the gross-out, eeriness, and the uncanny. This week, I wanted to focus on one of the most fundamental concepts in horror fiction: terror. Specifically, terror as distinct from horror.

This gets a bit confusing since we are using horror in two ways: as genre and as effect. But before horror was born, there was Gothic fiction. One of the founding authors of the Gothic genre, Ann Radcliffe, made a distinction between the effects of horror and terror:

“Terror and horror are so far opposite, that the first expands the soul, and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life; the other contracts, freezes and nearly annihilates them […] and where lies the great difference between horror and terror but in the uncertainty and obscurity, that accompany the first, respecting the dreaded evil?”

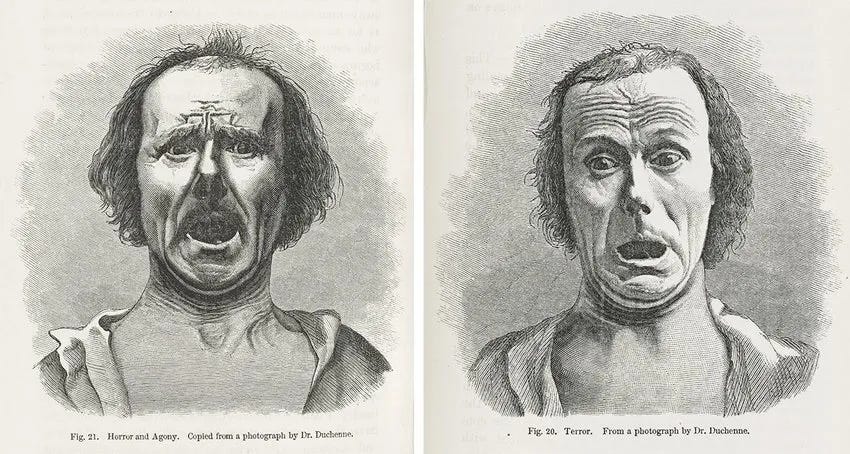

Horror, in this sense, is the feeling you get when you see the monstrous. When the knife-wielding killer stabs the hero, an oozing zombie hand grabs your wrist, or the ghost manifests to spook the living. Terror, on the other hand, is the feeling you get when you sense there might be an evil or otherworldly presence. Eerie sounds in the middle of the night. Odd figures lurking in the distant trees. The sense that objects in your bedroom have been subtly rearranged even though the door was locked. Horror is the bloody and blunt, and terror the subtle and creepy.

Radcliffe was in one way arguing the types of Gothic works she created were superior to the more violent and unsubtle Gothic books such as The Monk by Matthew Lewis. You can see a similar privileging today of high-brow “psychological thrillers” over low-brow horror films like slasher flicks. Whether this privileging is fair or mere snobbery, the distinction between the two effects on the reader (or viewer) is interesting. When you watch a horror film, there’s a different kind of fear in the moody and eerie build-up than there is to the bloody and violent reveal of the monstrous. Right? Horror doesn’t just scare us. It freaks, horrifies, terrifies, startles, weirds out, and creeps us out in different ways through different means.

It is worth noting that while Radcliffe says terror requires obscurity and indistinctness, she rightly warns against tipping into confusion. Confusion is especially marked, for Radcliffe, by a jumble of images—think of those annoying rapid-fire montages of “scary things” that many horror movies do—which don’t let us linger in fear but simply make us feel lost. To quote Radcliffe again: “confusion, by blurring one image into another, leaves only a chaos in which the mind can find nothing to be magnificent, nothing to nourish its fears or doubts, or to act upon in any way.”

Horror can be frightening, obviously, but in a way that is deadening. A jump scare shocks you, but the feeling is fleeting. Terror lingers. This is true in real life, not just fiction. When you walk down the street and see a dead rat you might get a momentary shock of revulsion. But if you wake in the night to the sounds of rats—is that rats or something else??—scratching in the walls, you will feel terrifyingly alive.

Terror lingers precisely because the mind cannot fully perceive what has activated it. Since terror comes from apprehension and obscurity, it (Radcliffe again) “leaves the imagination to act upon the few hints that truth reveals to it.” You are given a few hints of the monstrous, and your mind extrapolates. Because it is your mind, it conjures an image that is most effective at scaring you. In literature, this means each reader will imagine their own personalized awfulness.

I hope this doesn’t sound too highfalutin because it is also very practical. Think of how many horror films you’ve seen where the scariest parts are the scenes before the monster/killer/ghost/demon/zombie appears. And then when you see the creature, it is a letdown. The silicone or CGI monster rarely matches your imagination. This is why many of the most effective horror films rarely or never show the evil except perhaps partially in shadow.

The same is true in prose. The freakiest moments are often when we—or the character whose POV we follow—have only hints, traces, and suggestions of the supernatural or the horrifying. There are lots of authors, scholars, and critics who have written about the distinctive nature of terror. A few:

“Terror creates an intangible atmosphere of spiritual psychic dread, a certain superstitions shudder at the other world. Horror resorts to a ruder presentation of the macabre […] Horror appeals to sheer dread and repulsion, by brooding upon the gloomy and the sinister, and lacerates the nerves by establishing actual cutaneous contact with the supernatural.” —Devendra P. Varma

“Terror expands the soul outward; it leads us to or engulfs us in the sublime, the immense, the cosmic. We are, as it were, lost in the ocean of fear or plunged directly into it, drowning of our dread. What we lose is the sense of self. That feeling of ‘awe’ which traditionally accompanies intimations of the sublime, links terror with experiences that are basically religious in nature” —Barton Levi St. Armand

“The three types of terror: The Gross-out: the sight of a severed head tumbling down a flight of stairs, it's when the lights go out and something green and slimy splatters against your arm. The Horror: the unnatural, spiders the size of bears, the dead waking up and walking around, it's when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm. And the last and worse one: Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute. It's when the lights go out and you feel something behind you, you hear it, you feel its breath against your ear, but when you turn around, there's nothing there...” —Stephen King

Although horror and terror are considered different effects, they obviously tend to go hand in hand in narrative. The monster creeping outside the character’s door will normally burst through at some point. The shock of the horror has plenty of uses. The deadening effects of horror are in a way cathartic, allowing your mind to release its frightening fantasies. And, you know, narratively you tend to want the hero to confront the monster at some point.

That said, there are some works that manage to stay nearly entirely in the “terror zone” such as Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House or Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream.

One of the things that interests me about this concept of terror is how it plays into the strengths of prose. As a writer of horror fiction, I confess I’m often jealous of filmmakers. There is so much they can do with the visual image and sound that is difficult to pull off on the page. Can you have a jump scare in a novel? I like to think anything is possible, but surely it is difficult to pull off in text. It is also hard to match the grotesqueness of, say, Cronenbergian body horror, the vomit scene in The Exorcist, or the various macabre mutations of The Thing. Horror is immediate, concrete, and shocking. Visual media has an inherent advantage in creating such effects.

However, terror—as Radcliffe argues—is defined by obscurity and indistinctness. The visual has a difficult time with those. When we see the monster in a horror film, we see it. And audiences tend to want to see when they are watching something. Filmmakers have methods to keep things indistinct and obscure. Shadows, blurred lenses, angles, and so on. But there is only so long you can keep the monster hidden in a film. It must eventually appear. In prose, it will never literally appear as an image so even its overt appearance can be cloaked in obscurity and indistinctness—especially when you filter a scene through a character’s POV.

POV is of course key to achieving terror on the page. Readers tend to feel what our characters feel, at least if we’re writing effectively. And this is an advantage of prose. Literature can delve into the minds of characters. We can focus on the character’s psychological distress, and let the readers’ minds react in kind.

So, if you are writing horror for the page instead of the screen, consider staying as long as you can in the “terror zone.” Lean into obscurity and ambiguity, while taking pains to avoid confusion. Give the reader hints of the frighting. Markings of the monster. Suggestions of the supernatural. Strange sights. Distant sounds. Then, let the reader’s mind take over and expand in fear and fight.

If you’re interested in reading my own attempts at horror and terror, a few of my horror stories appear in Granta (online) and McSweeney’s (print). And one of my stories was illustrated in David Small’s brilliant graphic horror collection, The Werewolf at Dusk.

I also co-edited an anthology of frightening flash fiction tales called Tiny Nightmares that might interest any horror readers. It features Brian Evenson, Samantha Hunt, Stephen Graham Jones, Lilliam Rivera, Kevin Brockmeier, and many more.

I love the terror/ horror distinction, and it’s funny that over in the crime oriented genres, we simply call the former dread “suspense.” Hitchcock loved differentiating between suspense —hearing the tick of a known bomb—and mere surprise —the bomb going off, especially if the viewer was unaware of it. I’m other words, he drew the same emphasis between long-term psychological buildup of tension over sudden fleeting (often wasted) jump scare.

I thought that was an important distinction between horror and terror, between the visual and written forms of horror and terror. Terror can be in the atmosphere we create for our readers.When constructing terror, we allow the reader's imagination to work with our written words; they are pulled into our stories, participating in them. It is at least what I hope to achieve. Now that you mention it, I should work on that written attemp at jump scares too. Never really thought about it that way before.